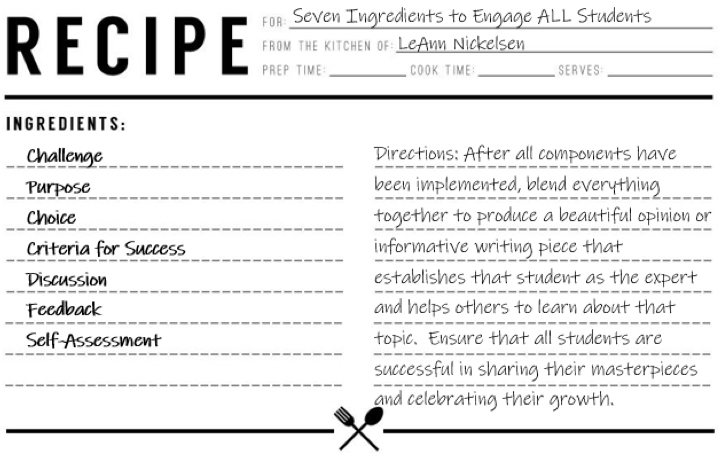

No matter your classroom, content, and students, the most effective way to increase students’ success is through deliberate lesson design – planning so all students are engaged and challenged on the journey of getting to “Got It!”. In order to do this, think of yourself as a Master Chef and your lessons as recipes. Use the seven ingredients below to maximize engagement and learning in your daily lesson plans.

What do these ingredients have in common? They all can engage and motivate students to learn at higher levels.

Researchers Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris found that total engagement means getting students highly involved affectively, behaviorally and cognitively (2004). I call these the ABC’s of Engagement. In other words, make sure your tasks engage students affectively (via emotions like curiosity, excitement, fun, interest, etc.), behaviorally (able to persist, asking questions, seeking resources, moving forward, etc.), and cognitively (depths of knowledge and complexity of thinking).

So, you’re probably wondering, what makes all of these “ingredients” motivating for students? How do they engage students affectively, behaviorally, and cognitively? And, how on earth can I implement them all? Let’s find out!

1

Challenge

Why?

The quickest way to reach high achievement and engagement is through selecting a challenging task. According to Hattie, planning for students to work at a high level of challenge has an effect size of .57 (any effect size that is .40 or more is significant for student learning) (2009). We also know that challenge and novelty have been shown to encourage brain plasticity and cognitive integrity, even having a protective effect into old age (Greenwood, 2010).

What does it look like in your classroom?

- Make it interdisciplinary: Add a reading/writing component to your math/science/social studies lesson. Add a historical/mathematical component to a language arts or social studies lesson. Use listening tools with social studies/science (Consult with your hall-mates to find an overlap in current or recent content!).

- Design tasks around key deeper-learning verbs such as: appraise, defend, describe, formulate, interpret, judge, justify, create, and/or prove. See the Depth of Knowledge Overview Chart for more ideas (Focus on Levels 3 & 4!).

- Interweave multiple standards in the same lesson: Go back to earlier in the year and pull some previous standards into the current lesson. This is a great reminder to students that everything they’ve learned with you matters! Plus, a quick recap of familiar skills can feel like an easy “win” for students.

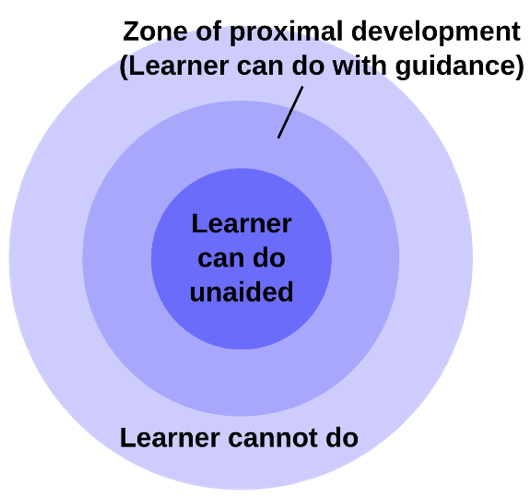

One critical part of choosing challenge wisely is keeping it in what Vygotsky called the Zone of Proximal Development (1978). The Zone of Proximal Development is any task that a learner needs guidance or support to complete. Teachers find that students experience great gains when they are challenged within this “just-right” zone. The best way to keep challenge within the Zone of Proximal Development is to rely on data. For example, use reading data from your school/district to be crystal clear on what different students can do unaided. Then use websites that sort texts by reading level to choose something that’s in the learners’ Zone of Proximal Development. Here are some great sites to get you started:

- www.readworks.org

- www.newsela.com

- www.newsinlevels.com (same article represented as different levels – perfect for early elementary!)

- http://www.fortheteachers.org/reading_skills/ (scroll down for leveled reading articles appropriate for upper elementary all the way through early high school)

2

Purpose

Why?

At the end of the school year it can feel like the main source of motivation in our classrooms is us. Unfortunately, providing extrinsic rewards can actually have a negative effect on motivation, especially on interesting tasks (Deci, Koestner, and Ryan, 1999). Instead, try focusing on the three big factors for student motivation: experiencing autonomy, seeking mastery, and believing their work is purposeful (Pink, 2009). When students believe their work is needed, wanted and purposeful for themselves and their community (and even globally), they just might go above and beyond!

What does it look like in your classroom?

- Students can produce incredible products when they work to create solutions to real world problems. Consider finding an issue that’s relevant in your local community and asking students to figure out a solution to it. In fact, many students using science to help the homeless, improve public health, and maintain biodiversity. You can help the assignment become more purposeful when you connect with the local community, state, or their personal lives. Relevance can promote buy-in and motivation.

- Let them choose the audience. When students get to choose who reads the writing or research project, relevance and purpose increase (yes, students actually are more motivated to want to write!). This leads us to the third ingredient…

3

Choice

Why?

We all respond well to having choice. It gives us a sense that we are the masters of our own fates – in control of our own days and, therefore, our own futures. Students respond especially well to being given choice at school. So much of their day is already decided for them that infusing opportunities for them to choose something that connects to their interests or emotional attachments gives us a huge return on investment. Keep in mind, the specific type of choice doesn’t matter as much as the students’ feelings about the choice. We get the highest levels of engagement when students’ choices help them feel autonomous and competent (Katz and Assor, 2007).

What does it look like in your classroom?

- Embrace choice that already exists. For example, instead of pre-selecting the fable for students to read, take them to the library and let them choose their own. Or, do a mini-lesson on how to Google well and let them see what they can find on the internet for their research (“safe search mode” on!).

- Give choice in the process. Does everyone need to turn in each of the components of the project in the same order / at the same time? Or could different components come in at different times? Who gives them feedback at each point?

- Give choice in the final learning product. For example, a writing assignment might not need to culminate in a traditional essay. Instead, it’s possible students could make their point by creating a YouTube video (to be posted or not), an Instagram post, or an online review. For even more depth of choice in product, check out Choice Boards.

4

Criteria for Success

Why?

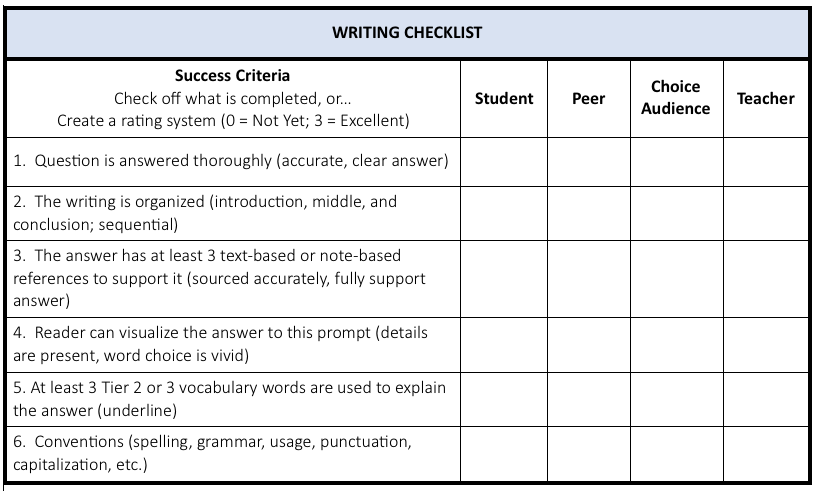

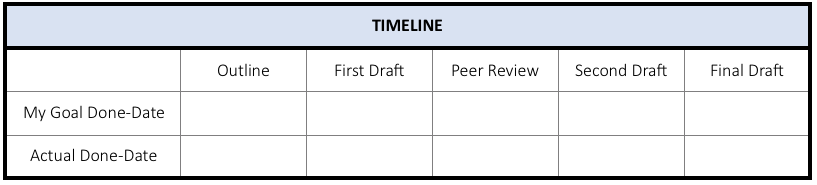

Have you ever had students turn in “less-than-quality” work? Have students ever asked you: What do you want in this project? Students often feel overwhelmed by everything that goes into successful completion of a larger project as they have not yet fully developed one critical skill: planning. Fortunately, there are two simple tools that can help them learn that skill, while also getting quality work turned in on time! The first is using a checklist to create a plan to get a project completed, which decreases stress in the brain (Masicampo and Baumeister, 2011). The second is sharing with students what success will look like alongside the learning goals, which has an effect size of .75 (Hattie, 2009). This is about 1.5 years of student achievement in one school year – well worth the time to create it!

What does it look like in your classroom?

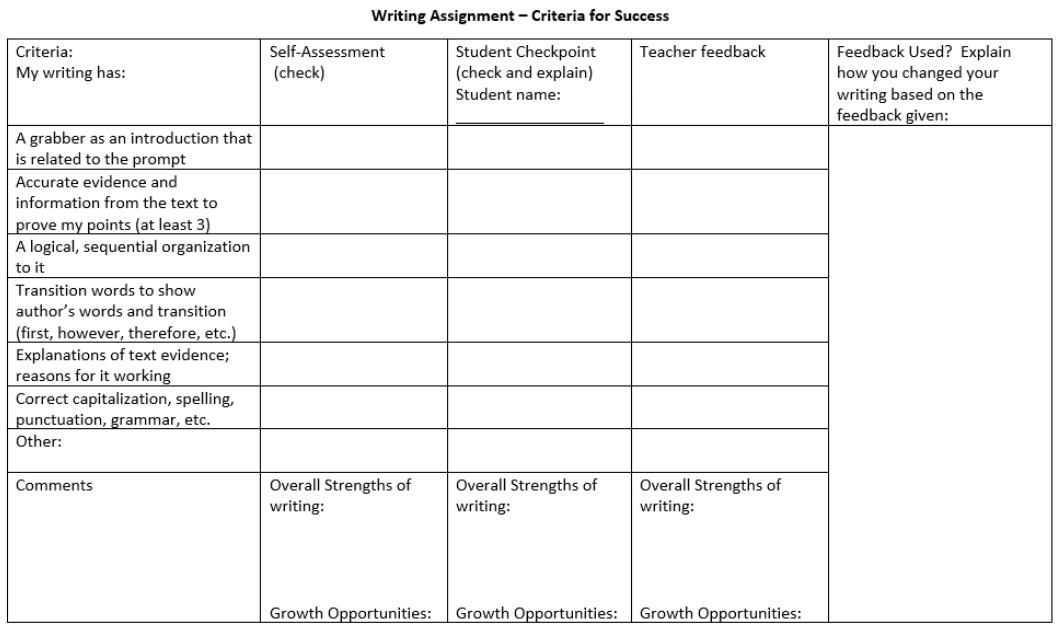

- Consider creating one student/teacher-designed Criteria for Success check-off sheet that will keep track of exactly what is expected and acts as a checkpoint along the way. This should contain both the qualities and quantities of what you want in the final product. Here’s an example that encourages students to choose one audience that will read their work (a top writing motivator):

Furthermore, consider exploring and evaluating an exemplar and non-exemplar of the writing or project against this same Writing Checklist. Working in small groups, students can identify what makes this example excellent (or lacking)? What could they have done better to improve this project?

5

Discussion

Why?

According to Hattie, classroom discussion has an effect size of .82 – that’s equivalent to over 1.5 years of growth in one school year (2009)! This is because class discussions allow students to deeply process their prior learning by both confirming what they accurately learned and revising any misconceptions. In order to maximize student engagement in and learning from classroom discussion, we must generate discussions that are structured, focused, open-ended, and authentic (Soter et al, 2009).

What does it look like in your classroom?

- One great way to lend structure and focus to your class discussions is through Socratic Seminars.Socratic Seminars allow students to arrive at deep levels of synthesis by interacting purely with each other. They’re deeply engaging and empowering because students “take the wheel.” Yet, students may need scaffolding to generate their own focused yet open-ended discussion questions to be used during a Socratic Seminar. Consider using question stems as a guide. Check out LeAnn’s Question Stars for the upper levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy here (Nickelsen, 2019)!

- Bonus! Socratic Seminars can have clear, actionable Success Criteria as well! Check out LeAnn’s Socratic Seminar Evaluation that can be used as a pre-Seminar guide and a post-Seminar self-evaluation.

6

Feedback

Why?

If your goal is to create big learning gains and to help your students stay intrinsically motivated during the learning process, then you will want to give students effective feedback. Hattie tells us that the best feedback has an effect size of .73, or equivalent to 1.5 years of growth (2009). To achieve maximum gains, feedback must be done within certain parameters. It must be clear, specific to the task, non-threatening, logically connected to students’ prior knowledge, and related to specific goals. Also, students should have the opportunity to implement the feedback as soon as possible (immediate is best). Furthermore, when we as teachers respond to students’ work and help students close their own gaps in their learning in real time, we call that the formative assessment process, which has an effect size of .90… effectively doubling the speed of learning (Hattie, 2009).

What does it look like in your classroom?

- Verbal feedback has the most powerful impact on student learning… but only if we hold students accountable for using it! When we check their work in progress, we pause and give feedback in the following way (Black & Wiliam, 1998):

Step 1: Notice the goals for the project or task and point out 1-2 details from the Criteria for Success (Where am I going?).

Step 2: What is the student doing correctly towards the learning goals (learning target or objective)? (Where am I now? Or, How is it going?).

Step 3: Help the student determine how to get closer to the goal by giving a prompt, resource, question, or referring back to the exemplars (How do I close the gap?).

- When we bring these steps together, the verbal feedback could sound like this: “Good stories have a beginning, middle and end. I see that your story has a beginning and middle, just like good stories. What would it take to write a powerful ending? Hint Hint – the Anchor Chart from yesterday has 5 ways to end a story. I’ll be back to see which one your chose.”

7

Self-Assessment

Why?

The brain loves autonomy and mastery, which is why student self-assessment is so motivating. Students can produce amazing evidence of learning when they reflect on their work using the Criteria for Success alongside feedback from other students and teachers. According to Hattie’s research, the effect size of self-assessment is 1.44, which is about 2.5 years of growth in one school year (2009)!

What does it look like in your classroom?

- What if we designed one tool for the task or project that had the Criteria for Success, space for feedback, a checklist of when feedback was used, and reflection or student self-assessment included? This would save everyone tons of time, and it would greatly impact motivation, engagement and student achievement. Here’s an example:

This example is the icing on the cake in that it integrates Criteria for Success, choice, self-assessment, feedback, and challenge. And if discussion and strong purpose was part of the task for this checklist, then you have all 7 ingredients!

Final Insight

Get excited about all that you can do by using the most impactful, engaging, intrinsically motivating tasks that will help students love learning every day! Use these seven ingredients to spice up any lesson and you will see a big difference in engagement, thinking and achievement!

Want to make this planning process easier?

Use my Magic Literacy Triangle Lesson Plan template! (HYPERLINK TO MY WEBSITE – MailChimp – Ashley will do this; under Resources)

By the way, The Magic Literacy Triangle is one of LeAnn’s most request trainings right now. Planning lessons in this way is moving schools’ literacy achievement off the charts! Contact LeAnn at leann@maximizelearninginc.com to request a description of this powerful training/coaching that will make a huge difference in student engagement and achievement. You can bring this actual workshop to your school – just ask LeAnn how!

Resources:

Black, P & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education Principles, Policy, and Practice, 5(1), 7-74.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic Rewards and Intrinsic Motivation in Education: Reconsidered Once Again. Review of Educational Research,71(1), 1-27. doi:10.3102/00346543071001001

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School Engagement: Potential of the Concept, State of the Evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge.

Katz, I. & Assor, A. (2007). When choice motivates and when it does not. Educational Psychology Review, 19 (4), 429-444.

Masicampo, E. J., & Baumeister, R. F. (2011, June 20). Consider It Done! Plan Making Can Eliminate the Cognitive Effects of Unfulfilled Goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/a0024192

Nickelsen, L., & Dickson, M. (2019). Teaching with the instructional cha-chas: 4 steps to make learning stick. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. New York, NY: Riverhead Books.

Soter, A. O., Wilkinson, I. A., Murphy, P. K., Rudge, L., Reninger, K., & Edwards, M. (2009). Corrigendum to “What the discourse tells us: Talk and indicators of high-level comprehension” [Int. J. Educ. Res. 47 (2008) 372–391]. International Journal of Educational Research,48(1), 77. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2009.04.001

Special Thank You to Tracie Steel, educator & contributing editor – best resource ever!