Reflect for a moment on one of your favorite teachers and think about why he/she was your favorite. Was it the teacher’s: Fun and engaging environment? Kindness to you and others? Belief in you and your achievement? Interest in you as a person? Care that you learned every single day? Or maybe a combination of these items? Whatever it was, your favorite teacher probably found a way to both teach you and connect with you as an individual. Your favorite teacher knew then what you know now: strong relationships can have a profound effect on student learning.

The Science of Relationships.

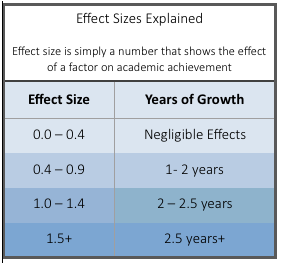

Strong teacher-student relationships are a keystone to academic success in school. Hattie (2009, 2012) found that the teacher-student relationship has an effect size of .72, which is about one and a half years of student growth. Research shows an 86% decrease in drop-out rates in schools where there are positive bonds between teachers and students (Lee & Burkam, 2003). Students aren’t the only ones who benefit from strong relationships; teachers benefit as well. One such benefit is the release of oxytocin. Oxytocin, commonly called the “cuddle hormone,” is a feel-good brain chemical that is released during positive, face-to-face interactions with humans. Hugging, shaking hands, and positive eye contact can release oxytocin quickly and the effects can linger for some time afterward. Oxytocin has many benefits, such as: staving off many psychological and physiological problems, breaking social barriers, inducing feelings of optimism, increasing self-esteem, overcoming fears, reducing pain, increasing generosity, bonding and building trust (Kosfeld, Heinriches, Zak, Fischbacher, & Fehr, 2005).

The effects of positive connections with others are more dramatic than we ever thought. Research in intensive care units shows one person’s presence can actually lower another person’s blood pressure. Scientists further found that one person can transmit signals that can change another person’s hormone levels, sleep rhythms, immune systems, and oxytocin levels (Lewis, Amini, & Lannon, 2000). The bottom line is this: we know today more than ever that humans are inherently social beings that pick up on very subtle cues. One person can have a powerful impact on another’s physiology, emotions and learning.

The Harmful Effects of Bad Relationships.

The unfortunate flip side to all of this is that negative relationships are a primary factor in students’ lack of success. For example, many students who do not wish to come to school or who dislike school cite disliking their teacher as the primary reason why (Cornelius-White, 2007). Poor or weak student-teacher relationships can cause any of the following negative effects: chronic elevated cortisol levels (the stress hormone which can shrink or kill brain cells and hurt memory skills), lowered thinking levels, impaired social decisions, and decreased desire to learn (Sapolsky, 2005). Basically, if great relationships can work miracles in lifting students up, bad ones have the same power to pull students down. So, knowing this, we ask ourselves: what concrete steps can we take to create and maintain positive relationships with our students?

1

Embrace Student Voice

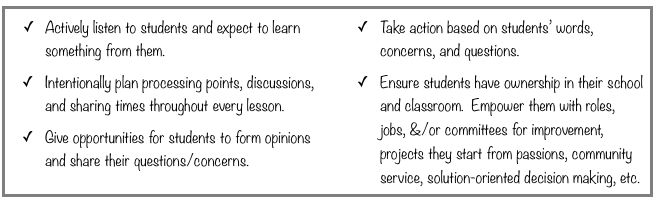

Many students like to talk. Luckily there’s a great way to use this to our advantage. The Quaglia Institute (2016) found that when students have a voice in their learning, they become seven times more academically engaged. That’s a huge number! Yet they also found that only about 50% of students felt that their teachers made an effort to get to know them and/or cared about their problems and feelings. So how can you make sure you’re in the top half? Here are some simple strategies to try:

For example, Janell Cleland (2016) starts the year off by asking her students to create a list of characteristics describing a teacher that they have learned well from in the past (nice, understanding, enthusiastic, funny, etc). She also shares her own list of traits that have helped students be successful in her class (positive attitude, open-minded, looks for the best in others, honest, etc). She posts both lists up in her room and even highlights which items from the lists both she and the students are using in the day’s learning objective. Then, at the end of each grading period, she and the students both give each other feedback on how well they are embracing the success traits. What a great way to show that we value our students’ input!

2

Co-Create Rules and Expectations

Rules and expectations are critical to the success of any classroom. As Rick Smith (2003) said, “Whenever students walk into the classroom, assume they hold an invisible contract in their hands, which states, ‘Please teach me appropriate behavior in a safe and structured environment.’ The teacher also has a contract, which states, ‘I will do my best to teach you appropriate behavior in a safe and structured environment.’” Co-creating rules honors students’ voices (creating a greater sense of buy-in) while still allowing behaviors to be managed proactively. Bonus: Students have more ownership of the rules they helped shape!

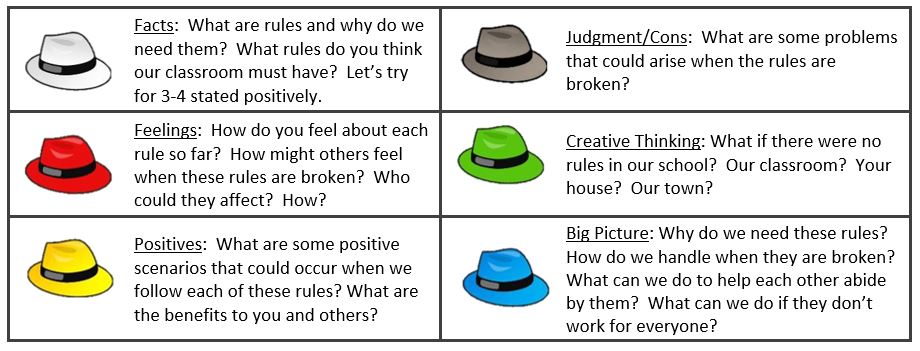

Personally, I took the students through a six question process called The Six Thinking Hats, designed by Edward Debono (1999), to help formulate the rules for our classroom. We came up with a beautiful list of rules that were posted and signed by every student. I saw more ownership and buy-in with the classroom rules, and, when a power struggle emerged, I gently remind the student(s), “You created these rules. These are your expectations for yourself.”

3

Set Expectations High for All Students

In education we talk a lot about setting high academic expectations, but what does that really mean? Put simply, it means that we expect ALL students to perform at or above grade level. The New Teacher Project (2018) completed a huge analysis on this factor and found that, “while more than 80 percent of teachers supported standards for college readiness in theory, less than half had the expectation that their students could reach that bar.” This belief played out in the classroom as follows: “teachers who agreed that their students could meet the bar set by grade-level standards tended to offer stronger assignments and instruction. Teachers who held the lowest expectations tended to offer lower-quality assignments. Those choices have consequences: In classrooms in the top quartile for teacher expectations, students gained five months of growth compared to students in classrooms in the bottom quartile for teacher expectations.”

Here are some practical steps you can take to help all your students reach grade-level expectations:

- If you have many students who come to you performing below grade level, focus your professional development on differentiation and scaffolding techniques so you can learn to build bridges as quickly as possible. (See LeAnn’s list of workshops on differentiated instruction.)

- If you’re not sure how much of the work you do in class currently is at grade-level, study your state’s standards for your own grade and a grade or two below. Run everything you ask students to do through the lens of those standards.

4

Establish a Joy Factor

There is a wonderful feeling when you walk into a classroom that is filled with joyful, smiling teachers and students! Time flies by as everyone actively engages in relevant, meaningful assignments. In a joy-filled classroom, students enjoy the learning and teachers enjoy the teaching. In Engaging Students with Poverty in Mind (2013), Dr. Eric Jensen says that every classroom needs to establish a “We are Family” mindset. Families take on each other’s problems, give ideas to solve them, hold each other accountable for goals that need to be completed, celebrate success, and encourage kindness among the members. John Hattie’s (2009, 2012) research shows that group cohesion and peer influences have a strong .53 effect size on student achievement. Furthermore, social bonding and trusting one another can even decrease the negative side effects of chronic stress by priming the brain to release oxytocin (remember this “feel good” hormone?) which, in turn, suppresses the stress hormone cortisol (Kosfeld, Heinriches, Zak, Fischbacher, & Fehr, 2005; Leuner, Caponiti, & Gould, 2012).

Personally, I love being in classrooms where students and teachers are laughing and learning at the same time. Laughter is hard to fake and is highly contagious! It involves highly complex neural systems that are largely involuntary (Provine, 2000). People who relish each other’s company laugh with each other easily and often, while the relationships where there is little trust often have the least amount of laughter among them. Could we say that the amount of laughter, smiles, and joy we see in a classroom could be an effective way to measure the quality of its relationships?

5

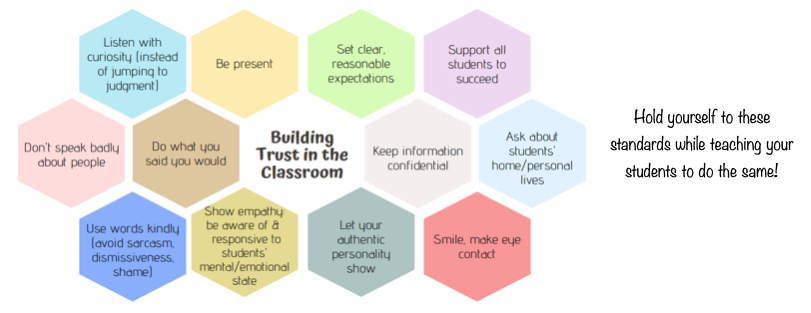

Building Trust

Trust is the emotional foundation of the classroom. It’s like the air we breathe: good, clean air allows us to thrive and flourish, but bad, dirty air suffocates and chokes us. Some people think that trust can be built by doing one-off exercises, but deep trust is built brick-by-brick in small, everyday actions. Here are some ways that trust is built in the classroom:

Trust takes on a new dimension when working with students from poverty. Because of a long list of poverty-related stressors, these students may have had limited or difficult relationships with their caretakers. When a student with a weak attachment history comes to a school without trusting relationships, it’s a recipe for disaster. If you notice that a student is hesitant to trust, try to remember that it may not be a direct response to you as an individual, but rather a self-preservation mechanism that he/she has had over time. Continue to show up for him/her every single day (you might be the first adult who ever has!). Every student can learn to trust with consistency and time.

Looking for more great ideas on building trust at school? Check this out!

6

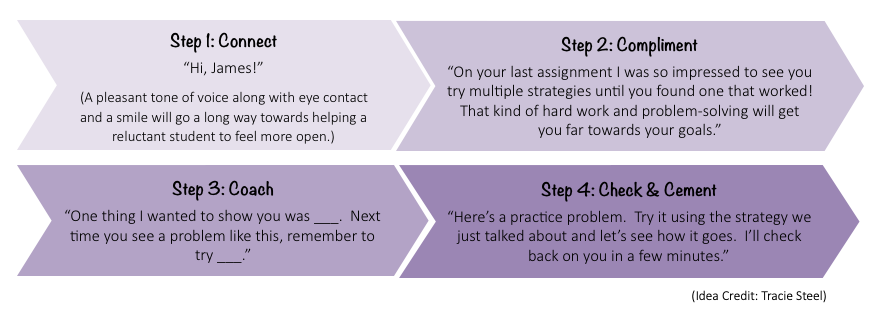

Respond to Students’ Unique Learning Needs

Students often progress towards learning goals at their own unique pace. One way we can be responsive to that is by pulling a small group of students (or an individual student) in order to respond to daily data. Responding to data by conferring with students one-on-one during guided reading, writing workshop, guided math, individual work time, or after tests shows that you are tuned in to each student’s learning growth and specific needs. Of course, you are incredibly busy & time never seems to be on your side – but think of this moment as an investment that will yield dividends for both you and your students for years to come. What if every teacher planned a two-minute, standards-based conversation that ended with goals to achieve those standards with two students every day? The growth that could come from this four-minute investment might shock you! Try this 4 C’s model to give “feedforward” faster:

I was once told by one of my students after reteaching him a math concept in a small group of about five students, “Mrs. Nickelsen, you are a much better teacher with a small group of students.” I was not quite sure how to respond so I chose to take it as a compliment. He was right! Our effect is so dramatic in targeted instruction with smaller groups of students because we analyzed the errors and thoughtfully determined the next steps to help students attain the learning goal. That action shows care, concern and a “let’s-close-gaps” attitude. My new book, Teaching with the Instructional Cha-Cha’s: 4 Steps to Make Learning Stick, has an entire chapter dedicated to how to make this differentiation step happen in the most effective way possible.

7

Use a Learning Profile

A Learning Profile is a file folder designed by each student that is full of surveys, interest inventories, attitudes about subjects, preferences for learning modalities, Multiple Intelligences assessments, and other content that explains who that student is socially, emotionally, physically and academically. They help you to see how students learn best, what their interests are, and what are their feelings and attitudes about the content area. Deeper Learning (2008), by Eric Jensen and myself, contains several pages dedicated to how to create this file folder for each student. This book has samples of reproducibles that you can use, website suggestions so students can do the inventories online, and many examples. Once we have all this information, we can use it not only to help us meet students’ learning needs but to also form stronger relationships.

If you’re looking for even more practical ways to differentiate based on students’ needs, check this out.

8

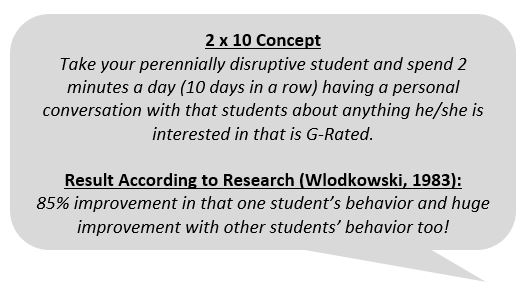

Assume the Best

What do you do if you’re certain that you’ve taught, practiced and re-practiced a rule or procedure yet you find a student not following it? Many teachers jump straight to consequences. While consequences are not always bad, before administering one, ask yourself: Is it possible that the student is using misbehavior to reach out to you for a positive connection or doesn’t know how to appropriately respond because the socio-emotional skill was not taught at home? Many students have learned (both at home and in school) that positive behaviors are expected but generally ignored, while negative behaviors get a lot of attention. Attention, connection and belonging are primal human needs that the brain can only ignore for so long. Once that limit is hit, students will attempt to meet it… whether we like how they do it or not! If we can remain calm in these moments and pause to consider if the student might really be searching for connection or need additional teaching/modeling of a valuable socio-emotional skill, we might find ourselves in the middle of an opportunity to reconnect and re-teach an essential skill.

Please know that this mindset is not grasping at empty excuses for our students’ behavior. Instead, it is using our deep knowledge of our students to understand their motivation so that we can respond to their behavior in the most effective way possible.

Conclusion

Your relationships with each and every student in your classroom make a dramatic impact on their learning. When students engage in positive teacher-student relationships they experience almost innumerable benefits, such as: adjusting to school more easily, wanting to attend school, viewing school as a positive experience, exhibiting fewer behavioral difficulties, displaying more positive social skills, and demonstrating higher academic achievement (Buyse, Verschueren, Verachtert, and Van Damme, 2009). My favorite saying that was printed in beautiful ink, framed and placed on my desk as a daily reminder of my power to build or break apart the relationships in my classroom is a great way to conclude this article. It’s a powerful statement that I hope you don’t forget about how our presence effects everyone around us.

Resources:

Buyse, E., Verschueren, K., Verachtert, P., and Van Damme, J. (2009). Predicting school adjustment in early elementary school: Impact of teacher-child relationship quality and relational classroom climate. Elementary School Journal, 110(2), 119-141.

Cleland, J. (2016). What About the Rules? A Lesson Plan for Building Trust First. ASCD Express, 12(2), 1. Retrieved from http://www.ascd.org/ascd-express/vol12/1202-toc.aspx

Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113-143.

De Bono, E. (1999). Six thinking hats. Boston: Back Bay Books.

Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Jensen, E. (2013). Engaging Students with Poverty in Mind. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

Jensen, E. & Nickelsen, L. (2008). Deeper Learning: 7 Powerful Strategies for In-Depth and Longer-Lasting Learning. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Kosfeld, M., Heinriches, M., Zak, P., Fischbacher, U., & Fehr, E. (2005). Oxytocin increases trust in humans. Nature, 435(2), 673-676.

Lee, V. & Burkam, D. (2003). Dropping out of high school: The role of school organization and structure. American Educational Research Journal, 40(2), 353-393.

Leuner, B., Caponiti, J.M., & Gould, E. (2012). Oxytocin stimulates adult neurogenesis even under conditions of stress and elevated glucocorticoids. Hippocampus, 22(4), 861-868.

Lewis, T., Amini, F., and Lannon, R. (2000). A General Theory of Love. New York: Random House.

Provine, R. (2000). Laughter: A Scientific Investigation. New York: Viking Press.

Quaglia Institute for School Voice and Aspirations. (2016). School Voice Report (Publication). Corwin.

Sapolsky, R. (2005). Sick of Poverty. Scientific American, 293(6), 92-99.

Smith, R., & Dearborn, G. (2003). Conscious classroom management: Unlocking the secrets of great teaching. San Rafael, CA: Conscious Teaching Publications.

The New Teacher Project. (September 2018). The Opportunity Myth. Retrieved from https://tntp.org/publications/view/student-experiences/the-opportunity-myth

Wlodkowski, Raymond. (1983). Motivational Opportunities for Successful Teaching. Phoenix, AZ: Universal Dimensions

A big thank you to Contributing Editor, Tracie Steel. Tracie Steel is an educator living in Houston, TX. She’s always found her greatest joy in working with students and has served as a middle and high school teacher, a district-level instructional coach/curriculum writer, and a brain-based learning trainer. She is most inspired to continue her work as an educational consultant by her two wonderful children who remind her daily what a gift and responsibility it is to raise up the next generation.