By Rick Wormeli and LeAnn Nickelsen, M.Ed.

Note: This article was first published in the Association for Middle Level Education (AMLE) Magazine in October, 2020. You can also read it here.

The concerns grew louder in early September of this year as many schools switched suddenly from in-person teaching to full-time, remote instruction due to a local COVID-19 surge: Students just don’t care about attending online sessions, and they aren’t turning in their assignments. Upon closer reflection however, it wasn’t so much a matter of students being irresponsible in their studies as it was a reflection of their sudden reality amidst the unrelenting coronavirus storm.

Not only were teachers battling the decline in student participation that began during last year’s emergency teaching and the typical proficiency slumps of summer, but their students were facing continued trauma with forced social distancing, evictions, canceled rituals/sports/performances/clubs, exacerbated inequities in access to schooling, illness and death of loved ones, parents’ job loss, and for some, newly abusive family life, increased opioid addictions, insufficient sleep, increased anxiety and depression, and a very real sense that those they trust to help them through all this were just as lost as they were. Teachers did the best they could, and did even better than they thought they could, but it still wasn’t enough for some.

Yes, we can expect a “COVID slide” in student achievement this year and in the years to come. In fact, “preliminary COVID slide estimates suggest students will return in the fall of 2020 with roughly 70% of the learning gains in reading relative to a typical school year. In mathematics, however, students are likely to show much smaller learning gains, returning with less than 50% of the learning gains and in some grades, nearly a full year behind what we would observe in normal conditions” (Kuhfield & Tarasawa, 2020).

Last year and now in the new year, teachers have responded heroically and creatively to these concerns, taking up the steep challenges of teaching students who are learning from their homes. They’ve created unique projects, re-vamped their instructional designs, collaborated on redesigning curriculum, provided students with materials, scheduled virtual learning lessons throughout the day, delivered meals along with lessons of the week, called students daily, taught lessons via online platforms while parenting their own children, added humor to learning experiences to create community, retaught content as needed, provided feedback in a variety of helpful ways, and some have installed MIFI (mobile Wi-Fi units) in neighborhoods and apartment complexes or driven buses into these locations so students could have Wi-Fi access for the school year. Of course, high poverty districts have even deeper challenges due to lack of supplies, food, medical care, and access to technology while also having more truancy issues and intense trauma generated by existing inequities. These same issues can be found in rural and urban communities as well (EdWeek Research Center Survey, 2020). Against the odds, educators have worked hard to meet their students’ needs, and they continue to do an amazing job.

Today, and for at least the next two years, there will likely be a need for remote instruction for some or all of our students who cannot attend in-person schooling due to lack of a viable vaccine and antibody tests, or who have suppressed immune systems, family issues caused by the pandemic, or other challenges. Teachers may not be able to be in their own classrooms themselves due to similar issues. The negative impact on the teaching-learning dynamic is stark and unsettling, and among the most concerning: the lack of student engagement with their own learning.

Many of us rely on time spent physically together, especially at the beginning of the year, to get know each other, create connections, and commit to one another’s success. And being together regularly, we adjust our interactions as we learn more about our students in order to ensure continued success and connection. With new students in each physically distanced school year, however, we are left adrift, as those opportunities are gone. Urgently, then, we look for insight on how to engage students in learning when we are so regrettably detached from them. Going forward, we suggest one of the most effective responses is proactive student agency.

What is Student Agency?

Student agency is when students self-initiate and persevere in their own learning through partnership with others and empowerment. To do this, they codesign goals, tasks/methods, and criteria for success for resolving challenges and accomplishing identified learning goals. Critical to these processes are self-reflection and feedback from peers and teachers, all helping students monitor their own progress and guiding the next steps in learning.

Agency, then, is not one event or factor, but rather a continuous cycle of growing and learning based on students’ interests, background knowledge/experiences, and what they perceive is meaningful to them. There is a passion, flow, and initiative to keep learning until goals are met or new ones are formed, even when confronted with serious hurdles along the way.

Teachers affect student agency significantly by questioning teacher-centered instruction and by planning instruction in such a way that elicits student voice, choice, and empowerment to act upon what is learned and valued. We’ve known for years that motivation is not something we do to students but rather something we create with them. When we partner with our students in their learning, both our instruction and their personal investment in learning improve.

In her 2018 article, “Part 1: What Do You Mean When You Say ‘Student Agency’?” Jennifer Davis Poon states how important it is to student agency to make sure goals are, “advantageous to the student,” continuing with the pointed concern that this, “calls into question what gets counted as a worthwhile goal and who gets to make that determination.” In addition, she reminds us that, “Once a direction is set, students don’t just gaze out the window of the bus. They drive. This…invokes existential concepts such as voice, choice, free will, freedom, individual volition, self-influence, and self-initiation.”

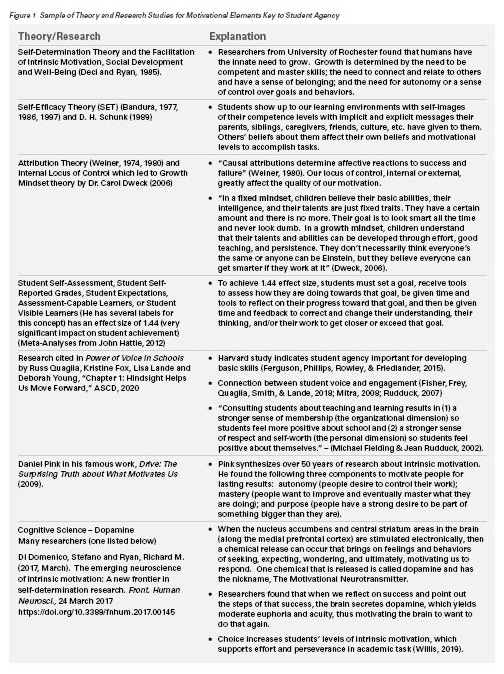

The positive motivational impact of developing student agency involves multiple elements, each with a significant theory and research base, let alone anecdotal evidence. A very brief sample of these studies are included in Figure 1.

The Bottom Line: Providing and designing opportunities of ownership for students as well as self-assessment, autonomy, celebration, descriptive feedback, knowing the why of learning, creating competence and multiple paths to mastery, and challenging our beliefs all contribute to intrinsic motivation. Bundled together, these components yield student agency.

Developing Student Agency, Especially in a Remote Instruction World

In his 2015 piece, “10 Tips for Developing Student Agency,” Tom Vander Ark, includes suggestions for teachers as they develop student agency, including caring for students’ emotional well-being but not so much as to coddle them, including their lives and perspectives in lessons while keeping students focused on learning goals, making instructional experiences interesting, facilitating cogent content, helping students with long-term memory processing, coaching students in their own self-monitoring, pushing students to think flexibly and substantively and helping them see the connection between their efforts and achieving things they value.

We propose a BOSS framework for partnering with students to create their agency in learning. We want the students to be in charge (the BOSS) of their own learning while we partner, facilitate, and coach them toward authentic learning experiences. Student agency grows while we help students foster beliefs and mindsets that elicit ownership, feedback, reflection, and success celebrations with next step action plans.

Beliefs: Cultivate self-efficacy and growth mindset. Since mindsets drive our behaviors all day long, this is where we start. It’s not so much a specific step, however, as it is an ongoing, constantly changing effort based on interactions with others, our subjects, our knowledge of students’ developmental processes and how they find meaning, and students’ attitudes about the subject. Beliefs and mindsets drive the rest of the student agency elements.

Ownership: Co-design goals that are challenging and needed, including criteria for success, and plans for achieving those goals through coaching. There is maximum emphasis here on the student’s voice and choice. The more that students co-design their lessons, learning tasks, and criteria for success, the more they take interest and engage in learning. We invite their ideas, interests, cultures, and ultimately, their voice and plans for accomplishing mediated goals, which becomes a partnership for helping students monitor progress, solve problems, and move their work forward. Dr. Russ Quaglia, founder of Quaglia for School Voice and Aspirations, synthesized valuable research about student voice value and their motivation levels (2016): He found that when students believe they have a voice in their school, they are seven times more likely to be academically motivated than students who don’t believe they have a voice.

We’ve compiled a list of ways to ensure students’ voices are heard throughout our schools and classrooms. Please see the specific practices for cultivating student voice and choice in the next section.

Self, Peer, and Teacher Feedback & Reflection: Provide co-designed clear criteria with students, modeling how to self-reflect and peer assess using that criteria. Provide time and techniques to guide students toward more reliable self-feedback and reflection that invokes thoughtful analysis of progress thus far, which then leads to helpful next steps in learning and growth, not comparison, status, or defensiveness. For specific principles and techniques on effective feedback, watch “Descriptive Feedback Techniques,” Part 1 and part 2 created by Rick on YouTube and available at www.rickwormeli.com, and see the work of Susan Brookhart, Bill Ferriter, Starr Sackstein, Garnet Hillman, Mandy Stalets, Shirley Clarke, John Hattie, Connie Moss, Douglas Fisher, Nancy Frey, Joe Hirsch, James and Jill Nottingham.

Success Celebrations and/or Next Steps Action Plan: With dopamine’s help, success breeds success. So, let’s model how to reflect on success, even celebrate it, and find meaning in every step—both large and small— towards achieving our goals. Let’s make progress visible, denoting milestones achieved. We can also model how to respond when any one or more steps were not successful. Here we promote the oft-shared interpretation of F.A.I.L. as, “First Attempt in Learning,” and see mistakes as stepping stones to success, not inescapable pits. As we positively affirm student progress and encourage students to do the same, they drop their singular focus on their weaker areas as a statement of their permanent plight, and instead, they see themselves as capable problem-solvers and goal attainers.

To move into a mindset that facilitates student choice and voice in their learning, focus on intentionality: Be ready at any moment to listen to students and expect to learn something from them. Plan information processing points, discussions, and sharing times throughout every lesson and take care to really notice what students say and do. Then, give their words, concerns, and questions serious consideration and react in a way that demonstrates that their voice merits response from those who care for them. This is deeply validating.

As we move through our lessons, whether they be done remotely or in person, we can invite student voice and choice, implementing practices that give students a stake in their own learning environment, topics of learning, and progression.

Classroom Management Tools that Invite Choice and Voice

When students experience voice opportunities, they are more likely to experience value and self-worth which in turn builds self-regulation and behavior management (Quaglia & Corso, 2014). When teachers give multiple opportunities for voice, they are declaring that they have enough respect for students that they want to know what they are thinking. It takes time, effort, and intentionality to build trusting relationships with mutual respect. Here are a few ideas:

- Give weekly proof that you know them as individuals and honor what they bring to learning’s table. This includes spending time getting to know them outside of the basic interactions in our lessons and integrating what we know of their lives and culture into our lessons. It’s worth the extra effort here.

- Empower students with specific roles in learning and classroom management, including responsibility for materials management, work updates, curating web content, committees for improvement, community service, resolving conflicts as they arise, and arranging for guest speakers/ trainers to do presentations for the class.

- Constantly invite students to design and take social and emotional climate surveys to improve the school and classroom.

- Provide learning experiences in which students “try on” different voices as they explore this growing element to their identity. Allow them to change their voice if they feel what they are doing isn’t their genuine selves or is a little too revealing. For example, they might initially explain a science concept using scholarly words and phrasing that sounds like a newscaster, but it doesn’t really sound like them, so invite them to describe the concept as if explaining it to their younger brother, using familiar words and comparisons. In some projects, they can make responses based on specific models of writing, thinking, and art, and in other projects, use different models in those same areas. Eventually, they outgrow these models and start using in their own voice the elements of those models that resonate most with how they’d like to be perceived.

- Ask them to create their own Learning Profiles to determine their interests within upcoming units, their learning preferences, how life is going, etc. When you take the time to care and truly want to understand how they are doing (personally and in school), student agency forms.

- Allow students opportunities for flexible seating, standing when they need to stand, or moving to a better location to see or hear the learning. As we teach our students about their brains and how important blood flow to the brain is, we hope they can take care of their movements without distracting others (yes, there will need to be parameters around these opportunities).

- Explicitly teach leadership skills so students can be better decision makers to solve community, school, and classroom problems.

- Consider using restorative justice techniques for classroom discipline. See https://edut.to/3jJidiH and https://bit.ly/358ghwe

- Build executive function skills. For more on this, see, “Looking at Executive Function,” (AMLE Magazine, August 2013).

Content Acquisition and Processing Ideas

When schools increase the amount of student voice in changing curriculum and instruction, research found that student learning improves (Oldfather, 1995; Rudduck & Flutter, 2000). There are many ways to improve student voice while planning lessons, units of studies, and assessments, and when determining the criteria for successful learning:

- Invite students to choose topics of personal interest with which you can integrate your subject standards.

- Create a pre-assessment, interest survey, or idea contributor before you start the unit in order to know students’ background knowledge, their passions within the unit’s topic, questions that intrigue them, and ideas that would make the unit more relevant and fun.

- Prime their brain before units or lessons begin so that when you activate prior knowledge at the beginning of your lesson, all students will have something to activate. Activating prior knowledge also sends the message of respecting what they know and what they want to learn. It allows teachers to personalize the learning.

- Invite students to choose a favored technology to investigate and express their learning as long as it allows for clear representation of evidence of the standard.

- Ask students to moderate online discussions or curate Google docs and similar artifacts.

- Teach descriptive feedback techniques that they can use for themselves and with one another. Ask students, for example, to write a letter to you describing where their effort on a particular assignment matches the exemplar provided and where it differs. Place a dot at the end of a line of students’ writing or next to a mistake in a math problem (or use a simple highlighting swipe), to indicate a mistake is present, but don’t identify what the issue is. Ask students to identify and correct the mistake(s) made. You can also ask students to create item analysis charts they can use to reflect on their test performance, they can respond to the three basic questions of feedback: What is my learning target? Where am I now (or, what progress have I made so far?), and what do I need to do now to achieve my goal?, and they can see the fruits of their labor and their capacity to grow via the classic reflection on a newly learned school topic: I used to think…, but now I think….

- Ask students for proposals for the products they will create to demonstrate their mastery of a topic and accept those alternative products as long as they demonstrate the required evidence of learning.

- Let students decide which method or assignment to use to practice the newly learned content between now and the next class meeting.

- Help students build and maintain portfolios (e-portfolios) of their work over time, including reflections on each piece.

- As you include access to knowledge and sense-making in your lessons, ensure processing knowledge and meaning-making as well. It’s not just about memorizing the five protections under the First Amendment; it’s knowing our rights and our responsibilities when we’re stopped by a police officer for a traffic violation.

- Invite students to research a question of interest directly or tangentially related to the subject of your course right now. Let students co-teach, or actually teach, the full lesson or a sub-section such as vocabulary terms to classmates (with your facilitation, of course).

- Let them help design the criteria for success (the qualities of the formative assessment that ensure mastery of the learning target) for a project or learning task.

- Build a cause meaningful to students into the curriculum–something for which they’d like to advocate in their own lives or communities.

- Provide an audience for student demonstrations of learning other than you or students’ parents. Younger students make a great audience for older student’s efforts, as do community organizations, publishing/displaying students’ creative content, and recorded performances.

- Let students choose a contemporary novel for your novel studies or as a companion text to the assigned reading.

- Give students two sticky notes before the lesson begins and invite them to write two questions that pop into their minds during the lesson (this activity can be done before, during, and/or after the learning). Depending on student age, sort the questions into broader categories and design a plan to answer these valuable questions.

- Ask students to connect with a professional in the field in the subject area of your course and explore how course content is applied.

- Co-create Likert scales to see where students are with the learning tasks.

- Let students start out processing information or demonstrating learning one way and have the option to go a different direction if they get a better idea while working.

- Implement and maintain a robust exploratory program, inviting students to try new and different topics of interest over the year to get a sense of them and discover previously unrecognized interests and talents.

- Invite students to generate metaphors for the science, math, writing, engineering, art, music, health, government, legal, media, or philosophical concept you’re teaching and one of their favorite sports, hobbies, or passions. Alternatively, ask students to portray abstract ideas via physically constructed models.

- Ask students to add their own voice to projects and assignments: If we left their name off the project, would we know who created it?

- Teach students empowerment tools and encourage their application in their studies. For example, teach students about debate, deductive/inductive reasoning, and logical fallacies, then ask them to conduct debates and write argumentative papers incorporating those tools. Teach them how to paraphrase others’ work, memorize text/ information, how to capture gist (summarize) cogently, and how to think divergently and analytically using Webb’s Depth of Knowledge, Frank Williams’ Taxonomy of Creative Thinking, David Hyerle’s Thinking Maps, and Sketch-noting. Summarization in any Subject, 2nd Edition (ASCD 2019) by Rick Wormeli and Dedra Stafford is a great place to start, as is teaching students logical fallacies, which can be found here.

Let’s help middle school students be in charge of their learning to every degree we can so it is as relevant and engaging as possible. Student agency is built through our daily student partnerships, not by yanking students from afar on tattered ropes to which they cling and watching them bounce and skid along harsh pavement toward an anxious future. Distress, which many of us feel right now, is really chronic stress in which we feel out of control of our lives and learning. Facilitating student agency gives some of that control back to students, and hence, distress is mitigated and engagement resumes.

Teachers find students’ rising agency exciting as well. Heck, it’s a big reason we entered the profession in the first place: To watch students discover their own talents and soar. So, invite them in. William Blake (1757-1827) reminds us, “No bird soars too high, if he soars with his own wings.” Middle school is exactly the right place to build sturdy wings, launch bravely into the new breeze, and find hope in what’s to come.

To receive more ideas about making content memorable and high impact, please refer to LeAnn’s book Teaching With the Instructional Cha-Chas.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.84.2.191

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice–Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W H Freeman/Times Books/ Henry Holt & Co.

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

Davis Poon, J. (2018). Part 1: What do you mean when you say “student agency?” https://educationreimagined. org/what-do-you-mean-when-you-say-student-agency/

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum.

Di Domenico, S., & Ryan, R. M. (2017, March). The emerging neuroscience of intrinsic motivation: A new frontier in self-determination research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11(145). https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00145

Dweck, C.S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

EdWeek. (2020). What percentage of your students are essentially “truant” during coronavirus closures? [Data set]. https://www.edweek.org/ew/articles/2020/04/10/where-are-they-students-gomissing-in.html

Ferguson, R. F., Phillips, S.F., Rowley, J. F., & Friedlander, J. W. (2015). The influence of teaching. Beyond standardized test scores: Engagement, mindsets, and agency. http://www.agi.harvard.edu/projects/TeachingandAgency.pdf

Fielding, M., & Rudduck, J. (2002, September 12- 14). The transformative potential of student voice: Confronting the power issues [Paper presentation]. Annual Conference of the British Educational Research Association, University of Exeter, England. http://www.leeds.ac.uk/educol/documents/00002544.htm

Fisher, D., Frey, N., Quaglia, R. J., Smith, D., & Lande, L. L. (2018). Engagement by design: Creating learning environments where students thrive. Corwin.

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Kuhfield, M., & Tarasawa, B. (2020). The COVID-19 Slide: What summer learning loss can tell us about the potential impact of school closures on student academic achievement. NWEA Research. https://www.nwea.org/content/uploads/2020/05/Collaborative-Brief_Covid19-Slide-APR20.pdf>

Mitra, D. L. (2008). Amplifying student voice. Educational Leadership, 66(3), 20-25.

Oldfather, P., & Dahl, K. (1995). Toward a social constructivist reconceptualization of intrinsic motivation for literacy learning. Perspectives in Reading Research No. 6. National Reading Research Center.

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books.

Quaglia Institute for School Voice and Aspirations. (2016). School voice report. http://quagliainstitute.org/dmsView/School_Voice_Report_2016

Quaglia, R. J., & Corso, M. J. (2014). Student voice: The instrument of change. Corwin.

Quaglia, R., Fox, K. M., Lande, L. L., & Young, D. (2020). The power of voice in schools: Listening, learning, and leading together. ASCD.

Rudduck, J., & Flutter, J. (2000). Pupil participation and pupil perspective: “Carving a new order of experience.” Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(1), 75-89. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640050005780

Rudduck, J. (2007). Student voice, student engagement, and school reform. In D. Thiessen & A. Cook-Sather (Eds) International handbook of student experience in elementary and secondary school. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-3367-2_23

Schunk, D. H. (1989). Self-efficacy and achievement behaviors. Educational Psychology Review, 1, 173-208.

Vander Ark, T. (2015).10 tips for developing student agency. https://www.gettingsmart.com/2015/12/201512tips-for-developing-studentagency/

Weiner, B. (1974). Achievement motivation and attribution theory. General Learning Press.

Weiner, B. (1980). A cognitive (attribution)-emotion-action model of motivated behavior: An analysis of judgments of help-giving. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(2), 186-200.

Willis, J. (2019, September 30). Maintaining students’ motivation for learning as the year goes on. https://www.edutopia.org/article/maintaining-studentsmotivation- learning-year-goes