Most teachers I know echo a common refrain to me: There’s just not enough time! Sometimes they’re referring to the countless “extras” we manage as teachers, but, more often than not, they are referring to their time in the classroom. I completely understand why they feel that way! We have so much content to teach and, seemingly, so little time in which to teach it. But, in my experience, the real time-drain isn’t initial instruction; it’s having to go back and re-teach content that the students “should have” learned already. I find that excellent, well-planned, first time instruction that includes the highest impact strategies can decrease my reteaching time. In other words, if I teach with the brain in mind within my initial instruction, more students reach mastery of the Learning Target.

And it’s not just our time that’s at stake. All those lost minutes add up to a detrimental effect on our students’ long-term learning. In fact, The New Teacher Project found that out of the 180 instructional hours in a school week, students spent only 29 of those hours in strong instruction (2018). This gap is a major contributing factor in what is called the “Opportunity Myth.” That is, even though 94% of students report wanting to go to college (indicating a desire to learn) and students succeed on 71% of their assignments (feedback that communicates to them that they’re performing at standard), 40% of college freshmen perform so poorly that they must take remedial classes, an earmark that makes them 74% more likely to eventually drop out (The New Teacher Project, 2018). Clearly, there is a gap between what students need to know in order to be successful beyond the K-12 school system and the skills that they are walking out of that system with. Quality first time teaching with high standards in mind can close this gap.

Luckily, there’s a way to strengthen your classroom’s first time learning in order to cut down on re-teaching time, to deepen retention, and to prepare your students for the futures they desire.

Using Chunk and Chew to Maximize First Time Learning

1

Chunk (Instruct)

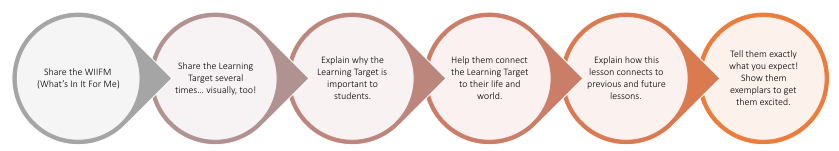

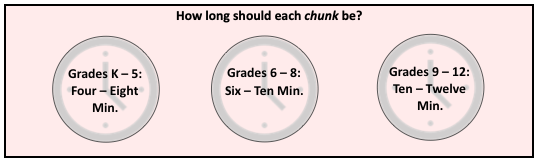

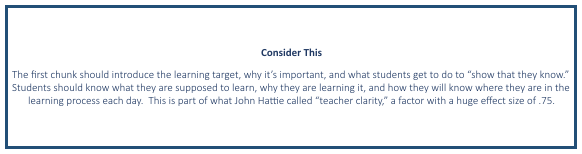

Strong initial instruction starts by taking our copious content that we need to teach in order for students to get to the learning target and chunking that content into meaningful, smaller, similar, inter-related sections. This helps students’ brains perceive each section as a coherent group of ideas. The teacher masterfully ensures that students are making these chunks meaningful and, therefore, more memorable.

One key strategy in creating strong initial learning is Activating Prior Knowledge (APK). APK has many benefits, including: “turning on” students’ background knowledge of the topic at hand, getting students focused on the current lesson, and giving the teacher valuable information about where the students are with the learning targets. APK happens right before the learning. You won’t have much time to change your instruction based on what the students share, but this powerful process helps students increase the connections in their brains and improve their memory.

NOTE: If you want more time to respond to where your students are with the standards, I suggest giving them a pre-assessment on that standard at least 1-2 weeks ahead of your lessons. Chapter 3 in my most recent book, Teaching with the Instructional Cha-Chas: 4 Steps to Make Learning Stick (Nickelsen & Dickson, 2019) has 10 examples that tell you step by step how to use them to change your lessons.

If you want your students to have the strongest possible retention of your instruction, be sure to also incorporate these four RARE factors (thanks to Dr. Eric Jensen):

R = Relevance. If content relates to the students’ lives, there is a greater chance attention and memory will occur (Liu & Hou, 2013). Students see or hear a reason to learn the content when you relate it to them; it makes it more meaningful. The brain wants to remember highly relevant content, so the nucleus basalis triggers the release of acetylcholine, a neurotransmitter that forms long-term memories (Luchicchi, Bloen, Viaña, Mansvelder, & Role, 2014). The brain must care about the content in order to store it. It must say, “This is so important, and worthy of learning: therefore, I will keep it!” Relevance and buy-in strategies need to be a part of every chunk. Here are some easy ways to create buy-in:

A = Acting it Out. Plan for some type of student movement in your chunks. Movement can have huge benefits! Namely, students who move more and sit less have: longer attention spans, faster processing speed, stronger connections to their learning, and increased performance on tests (Esteban-Cornejo, Tejero-Gonzalez, Sallis, & Veiga, 2015; Ratey & Hagerman, 2008). Don’t worry – your classroom doesn’t need to be all movement all the time. Even little episodes of movement can give you huge benefits! Here are some examples to try with students of any age: moving to a different location in the classroom, standing up and finding a partner to process with, sorting objects, combining or manipulating objects, acting out vocabulary words, role-playing a scene, or standing up while learning.

R = Retrieving. After students receive a chunk of information, pause and ask the students to retrieve the information (remember it from their minds only – with no help from notes, posters, partners, etc.) in a creative, engaging way (Agarwal, et. al, 2013). This helps them process and consolidate the information without overloading their working memories. Retrieval opportunities allow the brain time to make the content more meaningful and, therefore, more memorable (McDermott, et. al., 2014). Every time students retrieve information from their brains, (I call this a chew moment), the connections can get stronger. The more chews that students engage in to help them achieve the Learning Target, the more check points the teacher has as well. Each check point gives the teacher more opportunities to respond or change instruction by catching errors and misconceptions before they manifest (Hint Hint: Less reteaching!).

E = Making the Content Emotional. What is your earliest childhood memory? Think back and really try to remember it. If you’re like most people, the odds are that it is an emotional memory. That’s because of a brain structure called the amygdala, the emotional processing center of the brain. As many experts have said: The amygdala never forgets. Memories that connect to the amygdala (emotional memories) have a strong staying power in our brains. We can use the power of emotions in memory retrieval by evoking emotion within the lesson. For example, reading a short story such as Pink and Say by Patricia Polacco (1994) during a lesson about the American Civil War will evoke a strong emotional connection to the characters that can serve as an “anchor” for further learning about the Civil War. Joy, excitement, and wonder are emotions that can be worked into any daily lesson plan – it all happens in the planning!

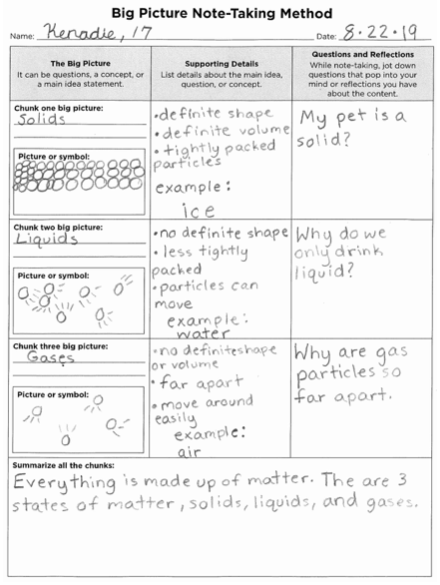

Here’s a great example of a chunking strategy that supports long-term memory: Big Picture Note Taking. Try having students do this individually to lead into a whole group discussion. This strategy benefits students as they organize content into smaller, interconnected chunks. (If you’d like a free template for this tool, please download it here.)

A very huge thank you to Rachel Swearengin at Manchester Park Elementary for sharing this amazing example of student work with me!

Bottom Line: When preparing your lessons, create the chunks that will be followed by chews. Create activities for buy-in and connections so your students are hooked for attention. Ensure there are ample memory tools (RARE) threaded throughout the lesson. While you’re teaching your chunks, make sure to gradually release your responsibility with the content so that they can eventually show you they can achieve your Learning Target all by themselves (independence). Plan for I Do, We Do, Two Do and You Do opportunities in each lesson so all students have more opportunities to get it to: “Got It!”

For more practical, engaging ways to chunk learning, check out my new book! It’s full of reproducibles that you can use in class tomorrow!

2

Chew (Learn)

Now that we’ve hooked students into the new information, they need to process it if they’re going to retain it. Some teachers think that learning takes place during the chunk (initial instruction) phase. While that phase is critical for drawing students into the new information, it’s the chew phase where learning really happens. Why? Because whoever processes the content remembers the content – processing the content with others creates ownership. In the brain, physical changes happen when effort and challenge are present: rearranging current and/or laying down new neural networks. These neural networks become more strongly locked in when students “get their hands dirty” with the content. Taking notes from a lecture is not enough for most students. Instead, they need the chance to test and refine their mental models in the laboratory of their own minds. Some examples include: mind mapping their notes, writing a summary about their notes, creating questions about their notes, designing a quiz from their notes, determining what missing pieces are still needed. This processing works best when done alongside fellow learners. Working together allows students to share insights, work through misunderstandings, and, perhaps most importantly, practice the skills of working alongside people that are both similar to and different from them. These learning opportunities are diminished in solo work, which is why solo work should be saved for later in the learning cycle (once concepts are more firmly nailed down). Truly, shared processing is a linchpin piece in the learning cycle. If you want to create longer-lasting, deeper learning, processing is the power tool!

If you want to create longer-lasting, deeper learning, processing is the power tool!

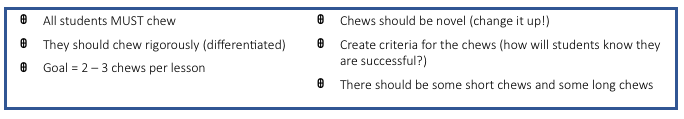

There are many different ways that students can chew information to deepen their learning. Here are some general criteria to keep in mind when deciding on what chews will have the highest possible impact on students’ long-term learning:

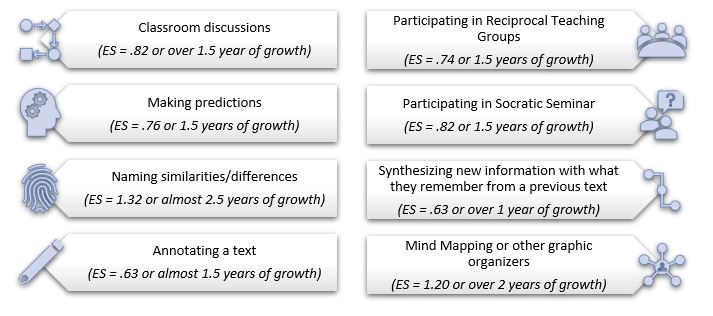

There are two main types of chews: Little Bitty Formatives (that take anywhere from a few seconds to a couple of minutes to complete) and Main Formatives (that take a much longer time and usually involve higher levels thinking). Sometimes the teacher gives one chew directive for the whole class and other times s/he gives students choices in their chews. Remember, choice drives engagement (Katz and Assor, 2007)! Below are some ideas for different types of chew activities, all of which have high Effect Sizes according to John Hattie’s work (impact on academic achievement):

Closing

Using high-impact first time learning techniques will drastically reduce your need to reteach. Chunk the learning by Activating Prior Knowledge and engaging students’ minds with RARE (Relevant, Acted out, Retrieved, and Emotional) initial instruction. Then let students take lead on processing the content in the chew step. This allows them to test their understandings alongside fellow learners to achieve the most accurate, deepest retention possible.

But it doesn’t stop there! There are two more steps to the learning cycle that drive retention even deeper: check (examine) and change (differentiation). Keep an eye out for my next newsletter, where we will delve into doubling the speed of learning by exploring those two concepts!

If you’d like to see more from LeAnn, visit her website by clicking here!

References:

Agarwal, P. K., Roediger, J. L., McDaniel, M. A., & McDermott, K. B. (2013). How to use retrieval practice to improve learning. St. Louis, MO: Washington University, Institute of Educational Sciences.

Esteban-Cornejo, I., Tejero-Gonzalez, C. M., Sallis, J. F., & Veiga, O. L. (2015). Physical activity and cognition in adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(5), 534-539.

Katz, I. & Assor, A. (2007). When choice motivates and when it does not. Educational Psychology Review, 19 (4), 429-444.

Liu, T., & Hou, Y. (2013). A hierarchy of attentional priority signals in human frontoparietal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(42), 16606-166616.

Luchicci, A., Bloem, B., Viaña, J. N. M., Mansvelder, H. D., & Role, L. W. (2014). Illuminating the role of cholinergic signaling in circuits of attention and emotionally salient behaviors. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience, 6, 24.

McDermott, K. B., Agarwal, P. K., D’Antonio, L., Roediger, H. L., III, & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Both multiple-choice and short-answer quizzes enhance later exam performance in middle and high school classes. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 20(1), 3-21.

Ratey, J. J., & Hagerman, E. (2008). Spark: The revolutionary new science of exercise and the brain. New York: Little, Brown.

The New Teacher Project. (September 2018). The Opportunity Myth. Retrieved from https://tntp.org/publications/view/student-experiences/the-opportunity-myth

A big thank you to Contributing Editor, Tracie Steel. Tracie Steel is an educator living in Houston, TX. She’s always found her greatest joy in working with students and has served as a middle and high school teacher, a district-level instructional coach/curriculum writer, and a brain-based learning trainer. She is most inspired to continue her work as an educational consultant by her two wonderful children who remind her daily what a gift and responsibility it is to raise up the next generation.

Want More?

LeAnn will be presenting at the following national conferences this year: